|

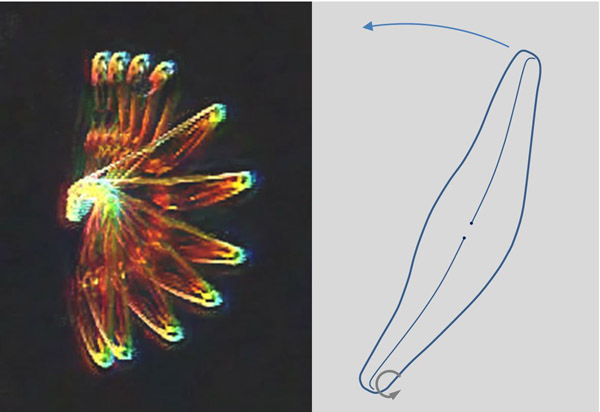

Paths of diatoms of the species Cymbella cistula (30x time lapse) |

Visualization of the movement by calculating the maximum over all frames and removing the background (click to enlarge) |

Curvature of the trajectories by the example of Cymbella

Diatoms of the genus Cymbella show symmetry with respect to the transapical plane, as assumed on the previous page. There is usually no symmetry of the valves with respect to the apical plane. One can distinguish a stronger arched dorsal and a weaker arched vetral side. The view on the valvar plane is sketched in the picture on the left. Incidentally, the two valves are not parallel. The typical Cymbella is thicker on the dorsal side than on the ventral (dorsiventral).

Most Cymbella spp. possess a distinct curvature of the raphe with a center of curvature on the ventral side, as shown in the sketch. A curved trajectory is therefore expected in which the centers of the curvature are also located on the ventral side. Actually, this is very often the case. A video of a cultivated species (Length: approx. 190 µm) can be seen on the left (30x time lapse). The video on the page for introduction into the movement and the associated visualization also show this curve direction of the path.

If the center of curvature of the path is always on the ventral side, the alternating sequence of clockwise and counterclockwise movements is given per se. If the path at the reversal points would not change the direction of curvature, the center of curvature would have to change to the dorsal side. The only difference to diatoms like Navicula is that one can recognize the curvature of the raphe already by the contour of the valve.

This would not be noteworthy if one did not also encounter a completely different movement. The video on the top left shows diatoms of the species Cymbella cistula (other posts provide information on size, sexual reproduction and formation of colonies) in which the center of curvature can be on the ventral as well as on the dorsal side. It often (but not always) keeps the sign of the curvature at reversal points (see diatom left). During movement in one direction a change in the curvature direction and thus a sigmoid path can occur in this species. In the video, the diatom on the left shows a half-turn around the apical axis at one location. Notable in this trajectory is the repeated change of the position of the center of curvature at the reversal points of the movement between the dorsal and ventral side. As a result, the diatom always moves with positive curvature. The movement was visualized in the image to the right of the video by calculating the maximum over the frames and and subsequent removal of the motionless background (using Fiji or ImageJ and manual correction). The uniform curve direction is marked by symbols.

It is obvious to carry out the analysis according to the methods of page analysis I in order to check whether there is a relation between the trajectory and the orientation of the diatoms. However it is important to remember that the assumption of a raphe near the connecting line between the apices is no longer exactly met. Therefore the behaviour will be illustrated on the basis of a few points of time first. In the animated picture on the left, several analysis steps are displayed at intervals of 5 seconds with periodic display. Only the first two segments of the trajectory from the video were used:

- The trackers were placed close to the apices and the video was tracked over two segments. The first picture shows the result.

- The images of diatoms at the same time intervals were copied over the trajectories.

- In order to indicate the orientation of the diatom, line segments (in red) were drawn through the apices.

- The images of the diatom were removed again so that the relation between the orientation of the diatom and the trajectories becomes better visible.

The first path segment is characterized by a center of curvature on the dorsal side of the Cymbella. It can be seen that the diatom orientation is in a good approximation tangential to the path of the leading apex (left ascending curve). Therefore, the model (see analysis I) is valid and the point P is located in the vicinity of the leading apex. So one can see that the diatom is drawn at a point near the leading apex and one may assume that here is a center of the force. The numerical analysis shows that this point is even a little outside the position of the tracker that means, almost at the apex. Looking closer at the diatom it is noticeable that the distal raphe ends are dorsally deflected. Some Cymbella sp. also shows hooked raphe endings. There is only a very small region of the raphe with a dorsal center of curvature. A picture of the valve of Cymbella cistula showing this curvature can be seen in the section on sexual reproduction (left in the picture gallery). Similar to Pinnularia, this area of the raphe seems to be essential for the movement behavior.

The direction of the activity of the raphe can typically change. Nevertheless, during the evaluation of the videos no movement could be found in which the Cymbella cistula is pushed from one point near the apex. Possibly the point P changes very rapidly its location when the direction of movement of the activity of the raphe is reversed.

In the second segment of the path a point P can only imprecisely be determined with the aid of the visualization. The proximate trajectories of the apices indicate a point P close to the proximal raphe endings. Because of the small distance between the proximal raphe endings it is not possible to assign it to any of the raphe systems. It could also be that a broad area of the raphe system is involved. With the presented methods this is not to be decided.

The rule of the alternating signs of curvature, which applies to Navicula and other genera, is not generally applicable because the point P can change between points on the raphe which have different directions of curvature.

Pivoting movements and direction of rotation at a dorsal center of curvature

In the video above, you see a Cymbella cistula on the right side which first moves on a small circular path with a center of curvature on the dorsal side. It then performs some pivoting movements in which the center of rotation is once at one end then at the other end of the diatom. Obviously, the radius of curvature of the movement at an apical center of force may be very different. This may be due to a more or less large contact area of the valve on the substrate, present mucilage or the activity of other raphe sections that are in contact with the substrate.

In an extreme case, the radius of curvature almost disappears and the diatom rotates horizontally about a pivot point near the apex by a certain angle. The raphe ending which is strongly curved or hooked towards the dorsal margin gives this species the ability to rotate on the spot. The picture on the left shows a pivoting movement by means of some superimposed images.

As a pushing movement from a point near the apex has not been observed, it is to be expected that the pivoting movement is always of such kind that the movable end of the Cymbella cistula moves in the ventral direction (see sketch). A diatome that moves along a small circle has the same direction of rotation. This direction of rotation is usually maintained, as one can recognise by viewing the pivotal movements in the video. After some observations however, it is obvious that there are also occasional reversals of the direction of rotation. But it does not change into a movement in which the diatom is pushed from the distal end of the raphe.

One obvious question is the influence of external conditions on the characteristics of the path. In the context of phototaxis it was shown that the times of the movement reversals depend on light conditions. It seems open to me whether there is also an influence on the change between dorsal and ventral center of curvature or the angle of rotation.